“”We don’t have a pulse on what’s happening in our change-portfolio,” admitted the Managing Director of an Asset & Wealth Management company, his frustration palpable. I probed further, “Is it a problem with data, tools, or skills?” He sighed, “We have an army of people producing reports daily, drowning us in PowerPoint decks for monthly steering committees and quarterly board meetings.” Just as I was about to delve deeper, he interrupted, “That’s exactly what you need to uncover”.

my conversations with the client

Managing Value – a complex challenge

The problem of poor or unsatisfactory strategic portfolio outcomes is a persistent issue to solve in many organisations. Despite years of experience, expertise bought from auditors & consultants and huge sums of money spent on sophisticated tools and technologies, the challenge remains unresolved

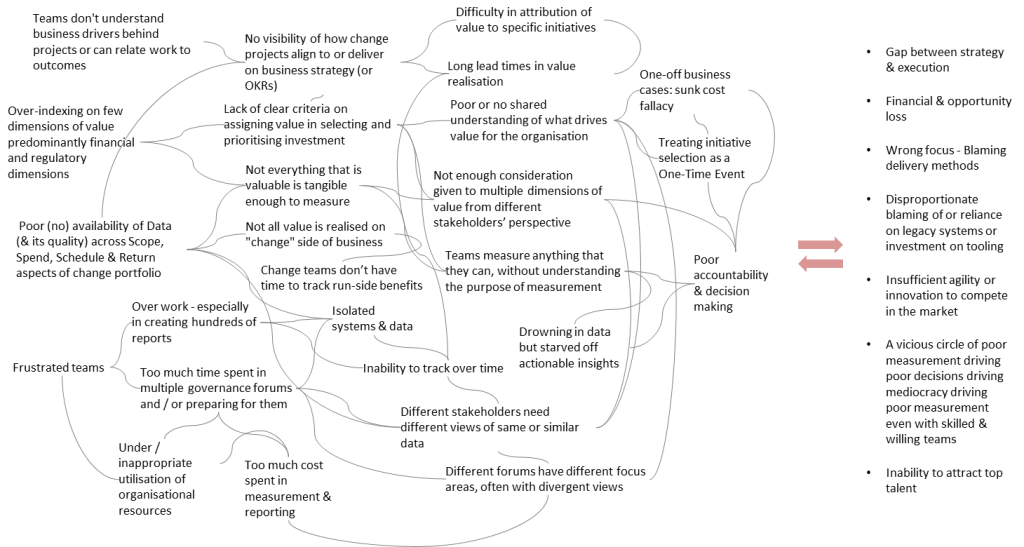

On one hand, there is a push to produce more and more reports to meet the demands of different stakeholders across the hierarchy. On the other, there is a severe lack of high-quality data to support decision making and optimise the current state or plan for the future. Despite the abundance of data and reports in many organisations, and the availability of tools to generate and support them, there is a significant lack of agreement on what “value” means and there is a severe shortage of actionable intelligence to drive outcomes of transformation initiatives.

Compounding this, the process of gathering, cleaning, summarising, reporting, and acting upon the data is time-consuming and prone to errors, leading to “decision latency and poor dependency management” – two critical challenges that contribute to strategic programme failures across industries.

When the Managing Director mentioned being “drowned in PowerPoint decks,” he wasn’t just speaking for himself. Many organisations experience this data overload, producing numerous reports but deprived of the high-quality data needed for effective decision-making.

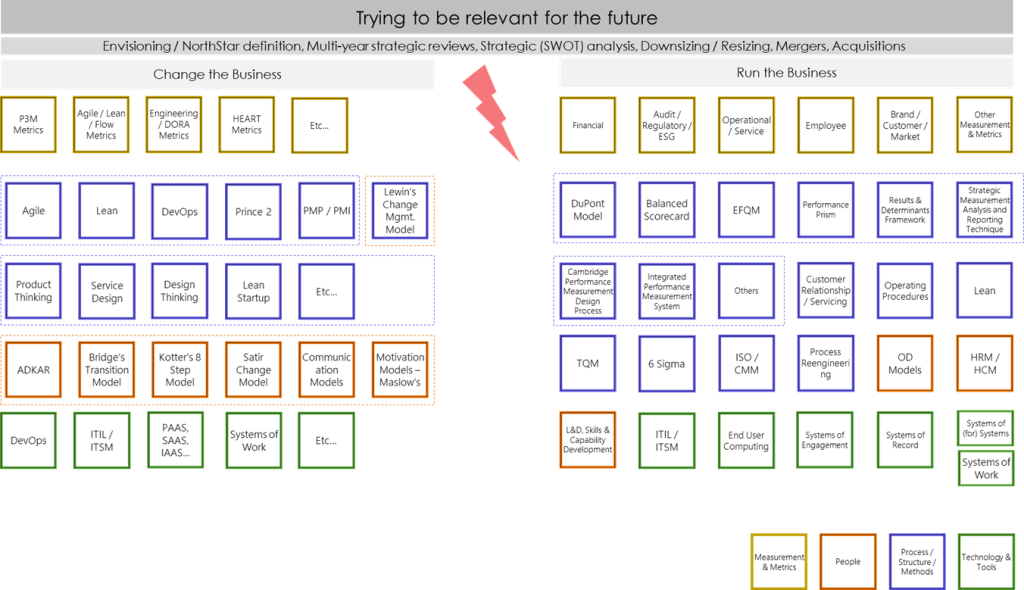

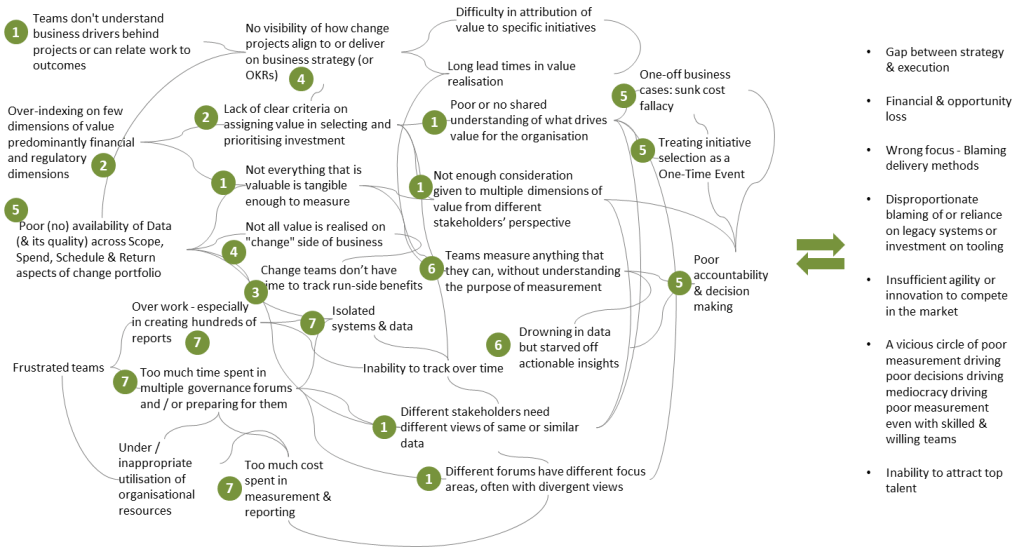

Digging deeper reveals that the challenge extends beyond data collection, reporting, or bureaucratic governance. The following simplified causal loop diagram illustrates the complex issues organisations face in managing the value of their project-portfolio investments.

Remember the Managing Director’s initial comment?—”We don’t have a pulse on what’s happening in our change-portfolio.” The challenges outlined above in the picture explain why. This is a complex problem, where it is difficult to establish exact cause and effect relationships, where everything seems muddled and foggy, losing the pulse.

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

Addressing the “wicked” problem

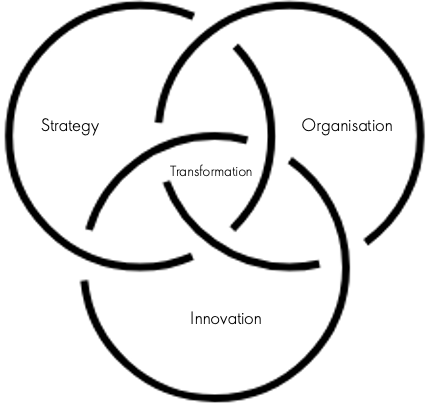

Addressing this wicked problem requires carefully applying multiple solutions and continuously monitoring the progress in desired direction.

There is no shortage of models, methods, methodologies, frameworks, and tools (see Appendix 1) designed to tackle the challenges of Value Management from various perspectives. The Balanced Scorecard, for instance, encourages us to go beyond financial indicators by including customer perspectives, internal business processes, and learning & growth metrics. Similarly, the EFQM Model provides a framework for organisational management focused on achieving excellence through customer, employee, and societal value. The World Economic Forum’s International Business Council (WEF IBC) identified a universal set of metrics to help businesses better demonstrate their contributions toward sustainable, long-term value creation

Yet, value management is hard and elusive in many large organisations. This created a need for a holistic framework that is robust enough in addressing the complex challenges mentioned above, but at the same time clear and simple enough to implement with practical solutions suitable for common contexts in large organisations, especially for those undergoing technology enabled transformation. This is how I see the framework’s end goal:

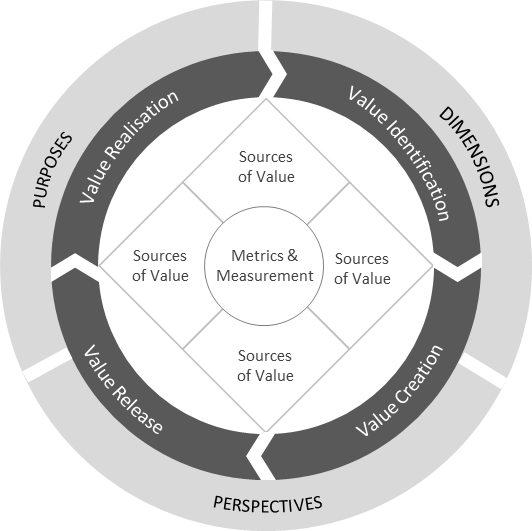

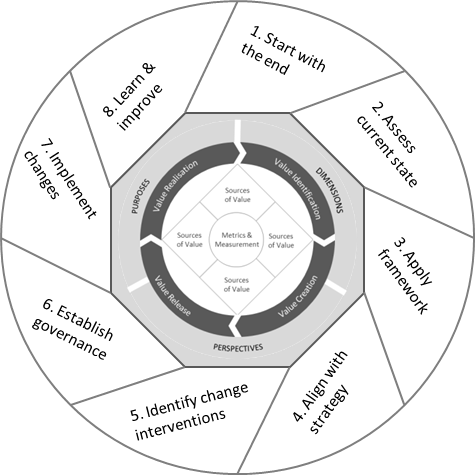

This framework shall enable us “define what we value as a business (Sources of value) from multiple stakeholders’ “perspectives” across multiple “dimensions” of value with clear indication on the “purpose(s)” of tracking & measurement across a “value lifecycle” appropriate for the organisation or endeavour at hand”.

Let’s now unpack the solution I suggested above:

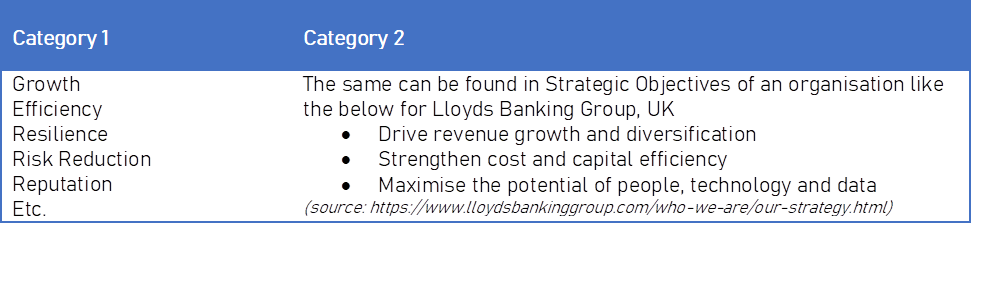

Sources of Value: At the core of an organisation’s economic-engine lies its sources of value, which are embedded in the organisation’s strategy and its offerings (propositions, products, services etc.) to the intended users. These sources reflect the unique capabilities, assets, or positions that an organisation leverages to generate economic benefits and stakeholder value. For example, a high street bank derives value primarily from the financial products it offers, such as savings accounts which attract capital and loans that generate interest revenue. Beyond these traditional sources, a bank might also find value in its customer relationships, brand reputation, technological innovation, and operational efficiency. Each of these components serves as a wellspring from which the bank can draw to sustain and grow its market presence. Typical sources of value would look like:

Sources of Value

Metrics and Measurement: These sources of value are measured through various metrics. For a typical Bank, few metrics they measure could include “savings or mortgage balance, cost-income ratios, number of complaints, number of customer service calls” etc. There will be hundreds of such metrics you’d find in any organisation.

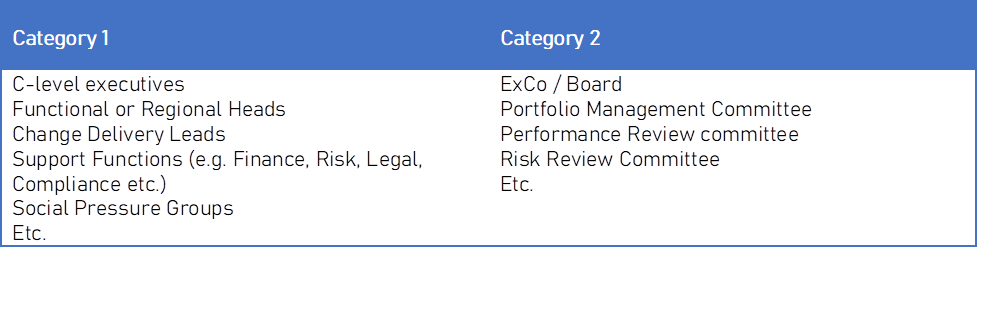

Perspectives of Value: (Business) Value is contextual. Value in an organisation is multifaceted and perceived differently across various levels and stakeholders. For example, C-Level Executive may prioritise strategic alignment and long-term returns, whereas Change Delivery Leads may focus on project feasibility, efficiency, and delivery within budget and time constraints. Sometimes, improving on one metric could adversely affect other critical metric, for example: increasing mortgages balance could be achieved at the expense of taking more risk. Recognising these diverse perspectives is crucial for holistic value management. It ensures that the organisation’s strategies and actions resonate with all stakeholders, aligning with their unique priorities and expectations. Typical perspectives you need to consider in an organisation are:

Different Perspectives of Value

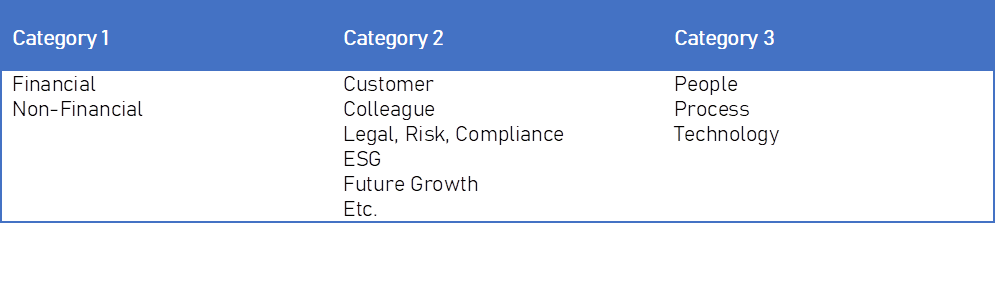

Dimensions of Value: The dimensions of a value are aspects of an organisation or programme or portfolio that are being evaluated. These dimensions are used to assess the effectiveness and success of the organisation or programme or portfolio. Organisations typically measure “financial” dimension of value. But this is not the only dimension that portfolio investments contribute to. Balanced Scorecard broadened these dimensions that many organisations are using for quite some time. Along with these, there are multiple categories of dimensions that organisations shall use. Table below summarises few such categories:

Different Dimensions of Value

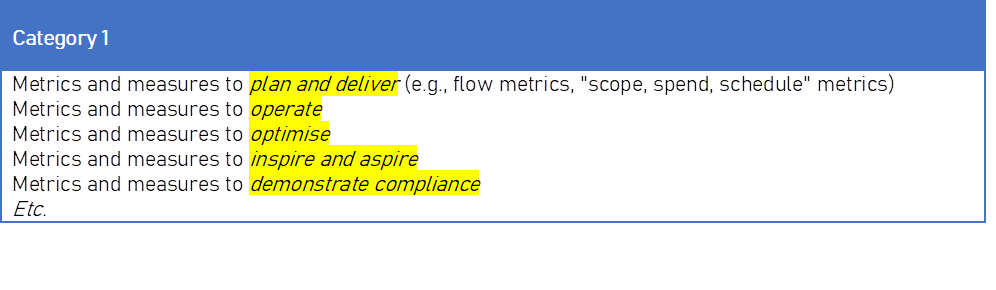

Purpose of Value Measurement: In Value Management, understanding the Purposes of Value Measurement is crucial. It defines the “why” behind the measurement process, directly impacting the “what” and “how” of data collection, analysis, and utilisation. An example from Agile-camps is “Team Velocity”. Though it is useful for team members, it is not meant to be used to compare how different teams are performing. Quite often, it is detrimental to change the purpose of measurement when making decisions. So, the “purposes of value measurement” help us determine what metrics and KPIs are being measured, how the data is being collected and analysed, and how the insights are being used. Typical purposes include:

Multiple Purposes of Value Measurement

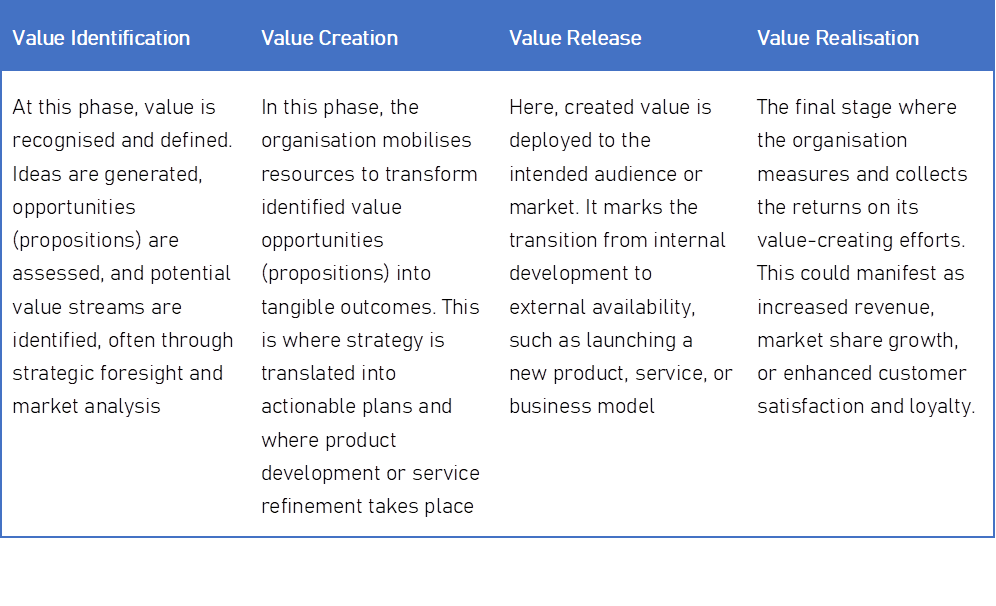

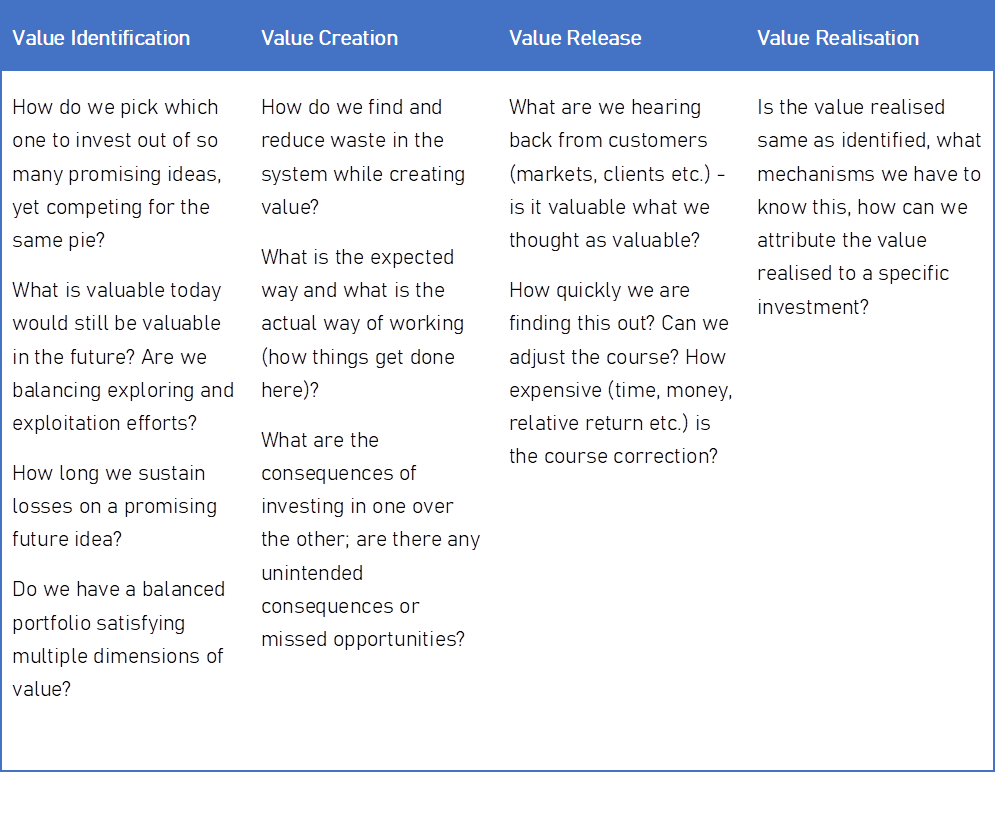

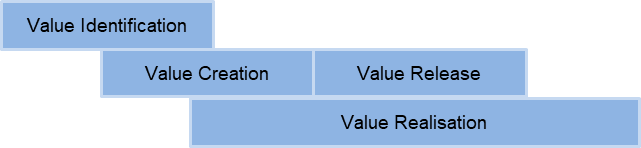

Value Lifecycle: Known by many names like “concept to cash and idea to impact”, a value lifecycle defines the stages within which an organisation manages and optimises the value it intends to create. The value lifecycle represents an organisation’s journey from the initial idea to its ultimate impact on the market and financial books, often spanning years in large organisations. Typical lifecycle stages are “Value Identification, Value Creation, Value Release and Value Realisation”. In many organisations, these are seen as “Strategic / Corporate Planning, Business & IT Solution Delivery, Operational Change, IT Operations & Business Operations (usually known as BAU, Run activities) etc.”.

Few questions to ask across value lifecycle

Quite often, these lifecycle stages are not sequential activities or stage gates, but typically overlapping activities yet distinct enough for us to act in a different way. These are not to be confused with Project delivery stages of software development lifecycles, though they can be mapped along these lines.

Here is a diagrammatic representation of the elements when you put all those together:

Value Management Framework – Artefacts and Use Cases

Apart from the conceptual understanding, such a framework shall provide “structure, processes, tools, and metrics” necessary to implement Value Management across the organisation.

A typical framework will include:

Value definition: The framework provides a clear methodology for defining and articulating value across the portfolio.

Value assessment: Framework comes with techniques for selecting and prioritising projects and initiatives based on their potential value contribution.

Value tracking: Framework provides few common Metrics and KPIs to measure, monitor, and report on value realisation including processes and tooling to support this tracking.

Value governance: Framework guides “decision-making” structures and processes to ensure efforts remain aligned with value goals.

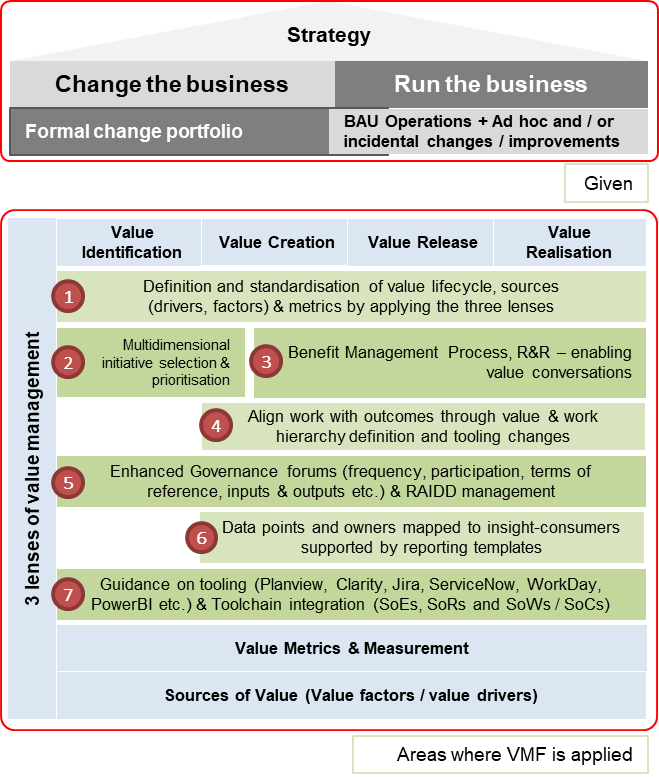

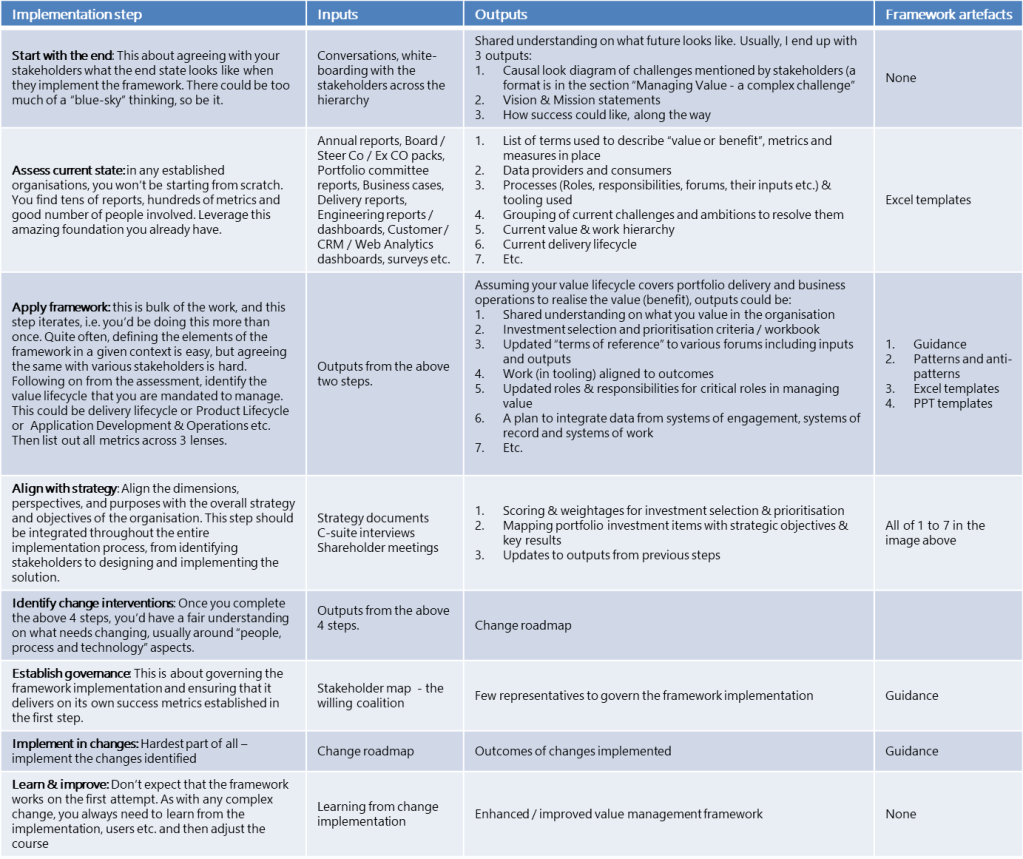

The below diagram shows how the Value Management Framework comes to life for implementation on the ground:

- Definition and standardisation of value lifecycle, sources (drivers, factors) & metrics by applying the three lenses

- Multidimensional initiate selection & prioritisation

- Benefit Management Process, R&R, Tooling – enabling value conversations

- Align work with outcomes through value & work hierarchy definition and tooling changes

- Enhanced Governance forums (frequency, participation, terms of reference, inputs & outputs etc.) & RAIDD management

- Data points and owners mapped to insight-consumers supported by reporting templates

- Guidance on tooling (Planview, Clarity, Jira, ServiceNow, WorkDay, PowerBI etc.) & Toolchain integration (SoEs, SoRs and SoWs / SoCs)

A detailed explanation of each of these artefacts is coming soon

The visual below highlights areas where framework elements could help address the complex challenges (numbers below map to the numbers in the above diagram):

For the practically minded

If you are convinced of the argument above and want to get going, below are the DIY implementation steps (loosely based on Deming’s Cycle – PDSA):

For the academically minded

Value: The perceived benefits, usefulness, and importance of something. In the context of “funded project portfolio”, “value” refers to the tangible and intangible worth of a project or portfolio delivers to the organisation and its stakeholders. Value is the primary reason organisations invest in projects, programmes and other activities.

One of the earliest known definitions of Value comes from Daniel Bernoulli, who stated that “value of an item must not be based on its price, but rather on the utility which it yields“. Much of the current thinking (definitions, processes, tools etc.) come from Lawrence D. Miles, an electrical engineer with General Electric (GE), which takes a “function” view for the utility. This can be seen in Society for American Value engineers (SAVE), The Institute of Value Management etc.

In my view value is more than “functional utility”

Key Characteristics of Value:

- Value is co-created. Both Producers and Consumers are required in order to create value.

- Value is inherently tied to the strategic objectives of the organisation.

- Value includes benefits but also considers a) cost of achieving those benefits and b) alignment with strategic objectives.

- Value is subjective

- Value is contextual / context sensitive

- Value is the “underlying context for decision making”

Value Management: The systematic approach to aligning projects and programmes within the portfolio to maximise their contribution to the strategic goals and priorities of the organisation. It involves:

- Identifying and selecting based on their potential to deliver value

- Prioritising the selected investments,

- Allocating resources accordingly, and

- Continuously monitoring and reassessing the portfolio to ensure that the anticipated value is realised

Value Management Framework: provides the structure, processes, tools, and metrics necessary to implement Value Management across the organisation. A typical framework will include:

- Value definition: A clear methodology for defining and articulating value across the portfolio.

- Value assessment: Techniques for prioritizing projects and initiatives based on their potential value contribution.

- Value tracking: Metrics and KPIs to measure, monitor, and report on value realization.

- Value governance: Decision-making structures and processes to ensure projects remain aligned with value goals.

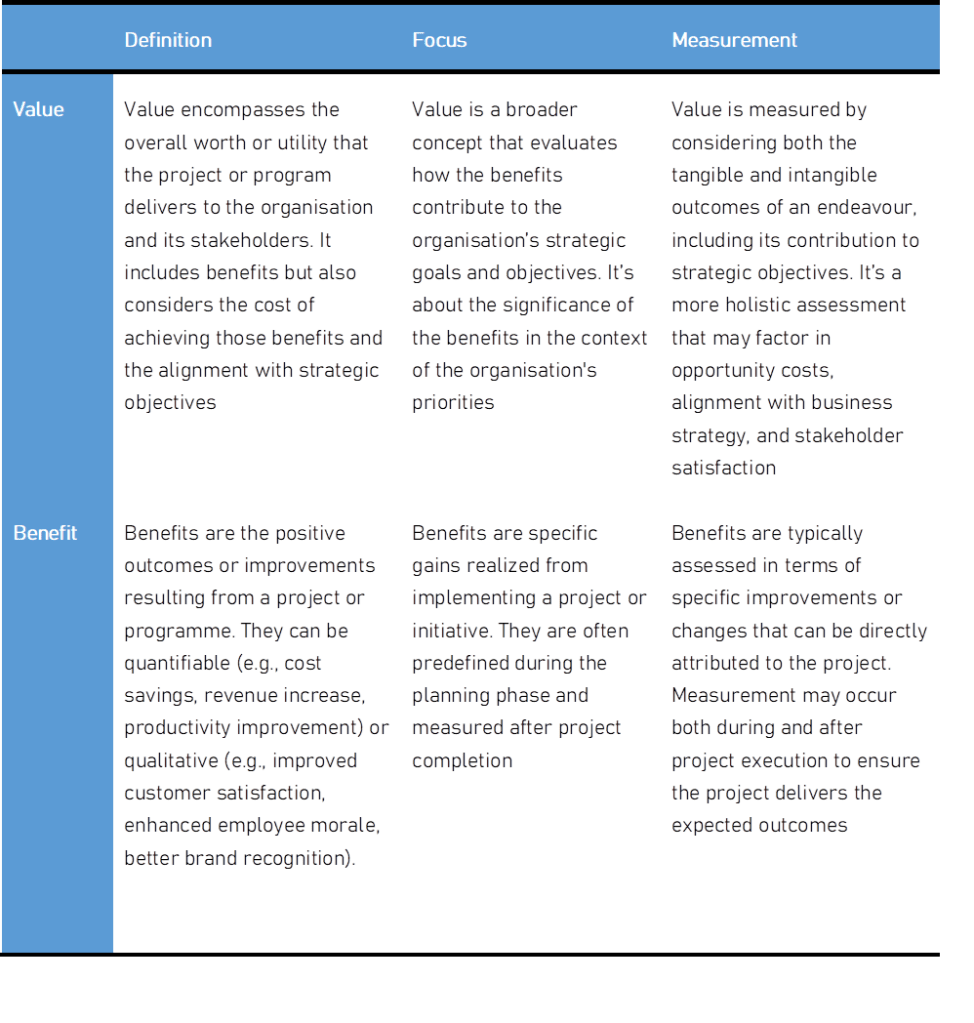

Value vs Benefit: In the context of Project Portfolio Management and Value Management, there is a distinction between “value” and “benefit,” though the two terms are closely related and often used interchangeably. See table below for further explanation.

Other popular frameworks dealing with Value and/ Or Performance

DuPont Model: The DuPont Model, also known as the DuPont Analysis, is a financial performance framework that breaks down Return on Equity (ROE) into three components: profit margin, asset turnover, and financial leverage. This helps businesses understand how their operations, asset management, and financial structure impact their overall performance.

The Results and Determinants Framework: The Results and Determinants Framework is an approach that focuses on identifying the key drivers (determinants) of organisational performance and the expected results. It helps organisations understand the causal relationships between performance drivers and outcomes, thus enabling better decision-making and resource allocation

The Performance Measurement Matrix: The PMM was developed by Keegan et al. (1989). It integrates financial and non-financial internal and external facets of business performance. The main strengths of PMM are its simplicity and integrated structure. The main criticisms of PMM include a lack of structure and detail, particularly in relation to making the links between different business dimensions more explicit, as in the Balanced Scorecard

The Strategic Measurement Analysis and Reporting Technique (SMART): SMART is a performance management framework that emphasizes the development of clear objectives, consistent metrics, and regular reporting. It encourages organizations to set specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART) goals, making it easier to track progress and make informed decisions

Integrated Performance Measurement System Reference Model (IPMS-RM): The IPMS-RM is a conceptual model that provides a framework for designing, implementing, and maintaining an integrated performance measurement system. The model emphasizes the alignment of performance measures with strategic objectives and the integration of various performance measurement tools and techniques.

Balanced Scorecard: The Balanced Scorecard (BSC) is a strategic performance management and measurement framework developed by Dr. Robert Kaplan and Dr. David Norton. It helps organizations translate their strategic objectives into a set of performance indicators that can be monitored and managed. The BSC is built around four key perspectives: financial, customer, internal processes, and learning & growth. By incorporating both financial and non-financial measures, the Balanced Scorecard provides a more comprehensive view of an organization’s performance and encourages a focus on long-term success

The Business Excellence Models of the European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM): The EFQM Excellence Model is a framework for assessing and improving organizational performance. It consists of nine criteria: five “Enabler” criteria (leadership, people, strategy, partnerships & resources, and processes) and four “Result” criteria (customer results, people results, society results, and business results). The model encourages a focus on continuous improvement and stakeholder satisfaction

The Value Measuring Methodology by Booz, Allen, Hamilton:

Information Paradox by Fujitsu Consulting

Appendix

Appendix 1: Models, methods, methodologies, and frameworks commonly found in many organisations